Note: This feature contains spoilers about Sifu’s plot and ending. I recommend you finish the game first before reading.

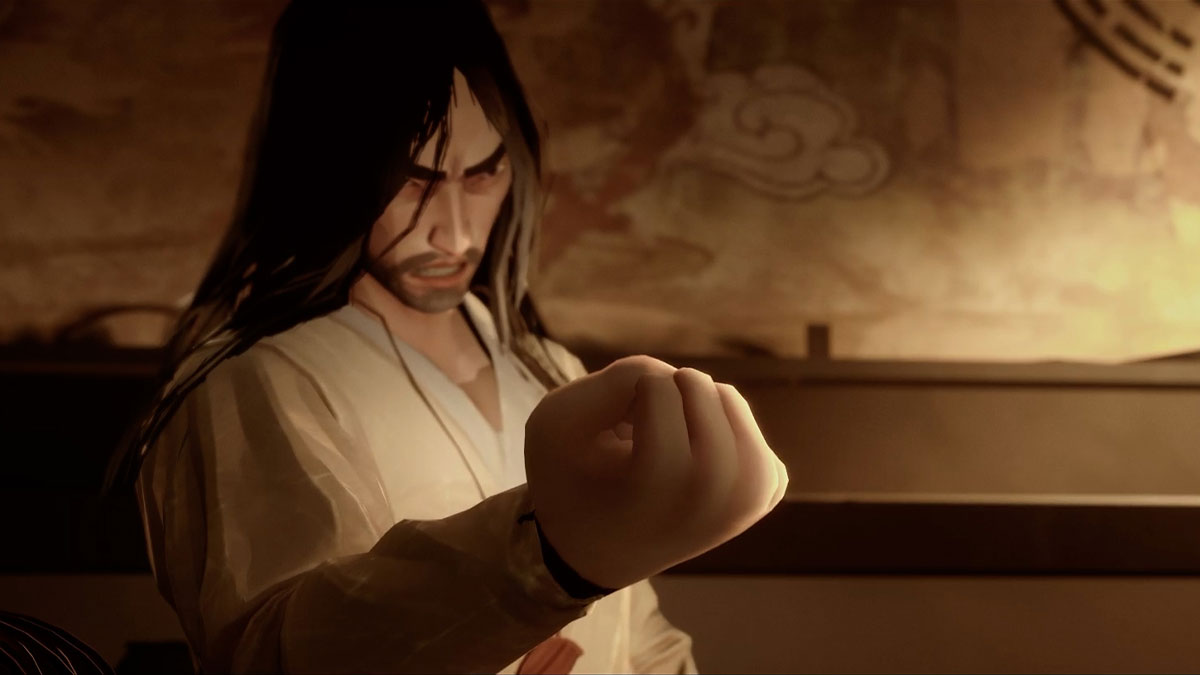

Sifu is a game about revenge. The opening moments see you in control of the villainous Yang, as his gang murders the father of the game’s protagonist. After that tragic death, you assume control of the unnamed hero. From that moment on, every move you make, every life you take, and every clue you add to your detective board are all in service of vengeance against the crew that orphaned you. But when you make your way through the ranks and end Yang’s life the same way he ended your father’s, you might feel unsatisfied. That’s because Sifu isn’t a game about revenge as a means to an end. Instead, it demonstrates that violence simply isn’t the answer. As I found the path to Sifu’s true ending, I learned a lesson in mercy through strength and discipline.

I came around a few different curves while playing Sifu. First there was the challenge of simply learning the ropes. I grasped the basics of Sifu’s systems and brute-forced my way through the first level or two, cheesing bosses and using as many shortcuts as I could find because I didn’t know any better way to win. Then, I found a new satisfaction in playing the way Sifu was meant to be played, with well-timed dodges, parries, and counters that got me through levels with far fewer deaths and way more martial arts moments straight out of the movies. The third revelation, however, was in discovering and practicing mercy the game wanted me to utilize. This was the greatest victory of all.

The first time you beat the final boss Yang, you get a brief, hollow ending. No credits roll. It’s clear that something is missing, and that thing is mercy. Revenge is only a momentary respite. True victory is proving to your opponent that you are better, then walking away to spare them. A kill would end things right then and there, but mercy means they live on knowing that you’re still out there, better than them. Killing will never bring anyone back, as many a story has taught us.

Sifu nudges you in this direction from the start with its detective board. As you collect photographs, documents, and keys across the game’s five levels, you start to learn more about each of your targets. They start to become less targets of vengeance and more sympathetic human beings. One of the final collectibles in the game is a document congratulating Fajar, the first boss, on being cured of a mysterious health condition. At some point, he visited The Sanctuary (the final level) and received treatment from Yang, the big bad himself.

Yang is the ultimate villain of the story, the one who killed your father and started this entire series of events…and yet, there is undeniably some good in him. He runs the clinic that cured Fajar, after all. The same goes for the rest of the rogues gallery. Sean keeps a photo of his deceased father in a lockbox, one that requires you to explore multiple levels to open. This is a prized possession, and it humanizes Sean — perhaps he’s even a fellow orphan like you. Kuroki knows loss too. Her hidden photo is of a lost twin sister, the motivation behind her life’s work. You realize that all these likeness she has crafted of herself aren’t vanity projects, but memorials to a sibling whose death is still very painful. The game’s five bosses aren’t just final obstacles for each level. They’re human beings who’ve suffered loss just like you.

The game’s demand for mercy hinges on this empathy in a narrative sense, but you still have to figure out how to spare your foes using the game’s mechanics. Doing so requires you to master their attack patterns in such a way that you can beat them without delivering a killing blow, breaking their defenses down multiple times instead. It’s not easy, nor is it always something I wanted to do. After multiple failed attempts to beat Sean the Fighter, I just wanted to break his big stupid pole over his big stupid head — I wanted revenge just as much as Sifu’s orphaned protagonist.

But that’s when I came around that third curve and became a true master of the fight mechanics. I got to the point where I could stroll through the levels with barely a scratch, smacking lackeys aside and beating bosses to a pulp. I was indeed the better fighter, and I proved it by sparing each boss and walking away. Letting them live isn’t a binary choice until the very last moment. You still need an active mastery of every boss battle to reach the point where you can actually choose mercy. You’re fully capable of slashing Fajar’s throat or choking Jinfeng with her own weapon, but you don’t. As their faces shift from fear to relief, you feel truly powerful as you walk away, knowing they won’t even bother to try to fight you anymore.

Enacting mercy isn’t just the best path for Sifu’s hero — it was also a lesson for me, the player. The game’s natural progression demonstrated that revenge isn’t the best path to victory. The deepest satisfaction came from humanizing the villains, mastering the flow of their fights, and having the discipline to spare the very people responsible for my father’s death. That’s real strength.

Published: Feb 11, 2022 12:51 pm