Locally Sourced is a zine that asks what games would look like if they were communal, not corporate

Shining a light into the murky waters of small-time game development.

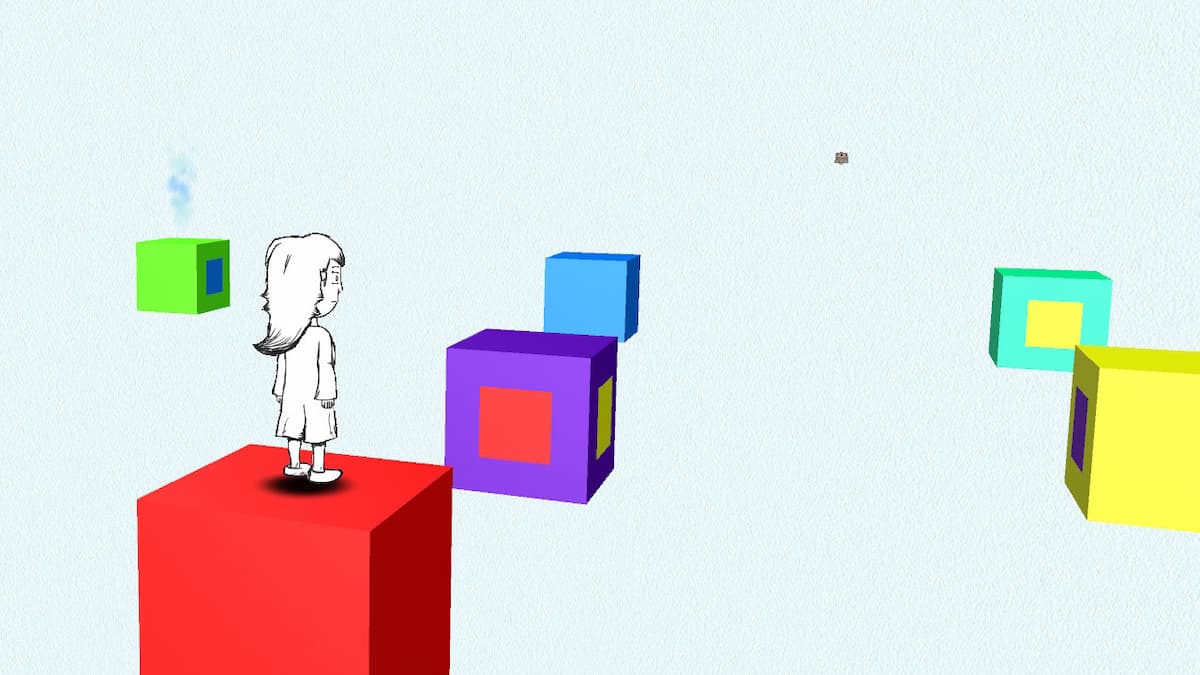

Image via Locally Sourced

Where are video games made and who makes them? Initially, that might seem like an easy question to answer. Game studios have little hubs in Vancouver, Silicon Valley, and in cities all over Japan. Video game production, however, is really an international affair. It’s easy to talk about specific cities or areas having specific music or film cultures. It’s a lot harder to do that with video games. Discs are manufactured, servers are maintained, and support staff labors quietly all over the world. As triple-A game development has gotten more expensive and intensive, labor has become even less concentrated in specific places.

To some extent, this diffusion is a natural consequence of global capitalism. In another sense, it’s a deliberate move — particularly for faceless developers who create countless HD assets as “assisting” studios. It’s harder to humanize or fight for the rights of workers and designers that only exist in the distance. This is part of what makes Rockstar co-founder Dan Houser’s statement that video games are “made by elves” so sinister.

Think Globally, Act…

Locally Sourced seeks to combat that facelessness. The electronic zine, based on the game-making group with the same name in Michigan, focuses on games and essays from local developers, writers, and artists. Michael Klamerus and Steven Zavala founded the group in the halcyon pre-COVID year of 2018. The two developers began to organize meet-ups, game demo events, and itch.io bundles. Klamerus told me in an email interview that the pandemic made it basically impossible to do in-person meetups indoors. “I thought the zine would be a nice way people could collaborate together on something,” said Klamerus. This is one of the zine’s delicious almost contradictions: It is based on a local community and something that can be made from anywhere.

That balance between seemingly contradictory ideas is a key part of what makes the project tick. The zine itself is at once a collaborative process and one filled with individual touches. The games vary in genre, from escape room visual novels to hand-drawn 3D platformers to Twine-like sacrilegious horror. This is, kind of, by design. “The wide variety of aesthetics in the zine really just comes down to me wanting the zine to be as stress-free to the contributors as possible,” Klamerus said. “All the games submitted were already previously made.” Their inclusion is more to show off the work of developers in the Michigan scene, rather than a curation of similar titles, or even games with the same aesthetic preoccupations. In fact, while Klamerus coordinated the zine, the contributors didn’t explicitly work with each other. Contributor Lily Valeen told us in an interview: “I didn’t know who else was contributing, and it was a nice surprise afterwards to see how many friends were featured!”

That is all to say, the games included in the zine feel as diverse as occupants of Michigan itself. A game called The Church of Cheesus Crisp casts the players as a pastor in a church. The congregation, a group of food people, asks the pastor to resolve their problems. They do this by playing a series of food-based minigames, a la WarioWare. It’s delightfully arch, silly, and charming. The game proclaims that “Sin Prevails” upon a game over, and seeing each new food person is a consistently funny visual gag.

Drew and the Floating Labyrinth feels like an early 3D platformer lost to time. It’s shockingly bare, almost relying on a kind of sketchbook game logic. Paramonsters and the Haunted Escape Room is a darkly silly Saturday morning cartoon, using its visual novel structure to build out fun and inventive puzzles. The personal highlight for me was Sacrosanct, the aforementioned sacrilegious horror. Depicting the fraught and troubling love story of a multiplicious divine and a relatively normal human being, it’s the kind of messy, profane fiction I live for. Interaction is minimal and choices are non-existent, but the prose is lavish, dense, and fractured. It’s unlikely that every game or article in the zine will interest everyone, but there is probably something for you here.

The Forgotten Realms

Still, a common thread runs through every part of the project: shedding a light on the forgotten and experimental parts of games culture. This is most obviously apparent in the written part of the zine. Lily Valeen wrote about ignored mobile games, like Gun Rounds, Magic Survival, and Golf on Mars. “The reality is that the phone is its own console… the most popular console in the world,” she told me over email. While mobile games can have an exploitative, monetized reputation, “[that’s] hardly unique to mobile. Plus, there are mobile games that avoid greedy monetization.” Games press can often overlook the entirety of what is a very complex space — Valeen sought to recommend some good games and cut through the noise.

Klamerus’s own contribution to the zine is a brief history of Hero MUD, a Multi-User Dungeon (think proto-MMO) that once ran on the servers of the University of Michigan. “With most MUDs from the 90s and earlier effectively being completely gone, describing the games and memories from the people who played them is essentially the only thing left that we can preserve of them now,” said Klamerus. The history of these complex games has been lost in the sea of multiplayer games since the genre’s heyday. He also hopes to write an updated version of the article in the future utilizing the game’s Usenet logs.

Zavala started an interview series for the zine, which he plans to continue with each issue. “I do the interview segments as a way to help promote the talented folks in our community and give them the opportunity to share their insights on game dev.” Rather than relying on the institutional wisdom of a GDC or TED talk, Zavala aimed to highlight the more local expertise of colleagues. However, he did admit that “It’s a little self-serving for me since it also serves as a good excuse to catch up with folks that I might not have had a real conversation with in a while.” There’s an idea here that I really like, that an artistic work can be “self-serving,” but still worth showing to other people. Not that a conversation with a friend can become “content,” but that it has worth and under the right context, that worth can be shared.

Community in Code

That idea is key to the ethos of the project. In some sense, these are all projects and impulses that might have existed without the zine format, perhaps on a blog or an itch page. Together though, the work gets elevated. Rather than individual islands, each game or article is an example of a community that is actively looking out for each other.

Locally Sourced is far from the first zine of its kind. Indiepocalypse and Knucklebone are both relatively recent examples of the formula. You could argue that the Haunted PS1 Demo Discs also broadly align. Klamerus specifically shouted out “zine communities like the Grand Rapids Zine Fest ” as inspirations. Locally Sourced still has its own particular charms, for reasons found in its name. If every community in the world made a similar zine, they would all be different. Locally Sourced, in its own small way, celebrates that.